WeWork made freelancers feel that they were on Google campus

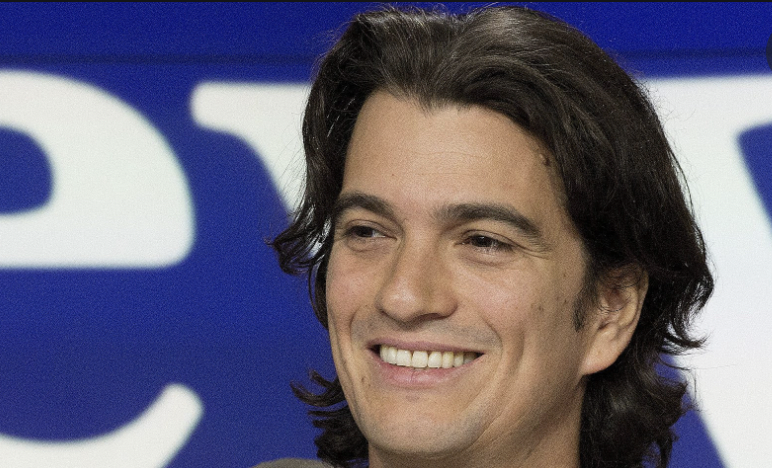

Grifters came to be called visionaries and high finance lost its mind. In 2001, charismatic Adam Neumann arrived in New York, the land of opportunities, after five years as a conscript in the Israeli navy, he transformed himself into the charismatic CEO of WeWork worth $ 47bn, within the span of 15 years. His long hair and feel-good mantras, six-foot Neumann looked the part of a messianic Silicon Valley entrepreneur. The vision he offered was mesmerising, and the radical re-imaging of work space, for a new generation. He called it WeWork.

Neumann, a hyperactive, hustling immigrant, disturbed one of the world’s largest asset class, convinced many people for so long, his unoriginal, loss-making start-up could change the world- and the laws of corporate valuation.

Before WeWork nearly collapsed Neumann turned his motivational T-shirts into Halloween costumes and brought WeWork within weeks of running out of cash, and raised more than $10bn at valuations peaking at $47bn.

A WeWork building – with its meditation rooms, pool tables, Vegan food stalls and aroma of small batch coffees could make insecure freelancers feel like they were on a Google campus with the gig economy sounded like freedom, where Silicon Valley seemed mere cool and creepy as thousands who were laid off in financial crisis were starting afresh.

Benchmark Capital the venture capitalist veteran that funded eBay and Instagram, bought what Neumann was selling, as did Harvard’s endowment, Fidelity and Alibaba’s Jack Ma. Masayoshi Son, The Saudi-funded SoftBank boss who liked to throw more cash at founders than they asked for and then berate them for not thinking big enough.

Wall Street Journal’s Eliot Brown and Maureen Farrell remind us in The Cult of We, “These investors considered the smart money” by Neumann telling them what they wanted to hear.

In September 2019, Neumann attempted to go public, he had sashed a cereal box full of marijuana on a cross-border private jet flight, and smoked so much that the oxygen masks came down.

When pointed out the conflict of interest in his ownership of some of the buildings WeWork leased, Neumann suggested news organisation should charge companies to have its journalist prepare CEO’s for tough questions they would face on IPO roadshow.

At one office party Neumann and colleagues lobbed the expensive tequila bottles they have been drinking from, deliberately smashing the glass panes separating his private office from the desks outside. Another Tequila fuelled event Neumann is said to have sprayed a fire extinguisher over Hony Capital’s John Zhao, one of his investors.

In Hong Kong, the authors capture Neumann stumbling through a starchy private club, blasting Jay-Z on a Bluetooth speaker and yelling “We are taking over the world”.

The authors reveal a decade of low interest rates and plentiful private capital allowed splashy start-ups such as Uber, Airbnb and WeWork.

To avoid disciplines of public market while private investors under wrote their losses for years. The line between a world changing dream and the selling of tall tale has long been vanishingly thin.

The Cult of We provides a useful reminder of how the billions the Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman had committed to the SoftBank Vision Fund were burning a hole in Son’s pockets when he decided to pour $4bn into a company that had previously raised only $1.7bn. Eighteen months later, Son who once predicted that Neumann’s company could be worth $10tn by 2028, slashed SoftBank’s valuation of the company to $2.9bn.

When Neumann bought a company that made whirlpool for surfers, nobody blinked.

WeWork was inflated by a glut of capital as participants in such bubbles are often intelligent even aware of madness. And for the corporate cult to succeed, its early followers need to believe that the cult leader can recruit enough true believers for them to get out at a profit.

As billion of funding dollars poured in, Neumann’s ambitions grew limitless. WeWork wasn’t just an office space provider, it could build schools, create cities, even colonise Mars. In pursuit of its founder’s vision, the company spent money faster than it could bring it in. From his private jet clouded with marijuana smoke, the CEO scoured the globe for more capital but in late 2019, just weeks before WeWork’s highly publicised IPO, everything fell apart. Neumann was ousted from hi company, but still was poised to walk away a billionaire. WeWork’s extraordinary rise and staggering implosion were fuelled by desperate characters in a financial system blind to its risks., with some of the biggest names in banking and venture capital buying the hype. What does the future hold for Silicon Valley unicorns

It is clear that nobody did more to inflate the WeWork bubble than the inventor turned telecoms mogul who almost lost his first fortune in the dotcom bust two decades ago.

The Cult of We: WeWork and the Great Start-Up Delusion, by Eliot Brown and Maureen Ferrell, Mudlark/Crown £20/$28, 464 pages.