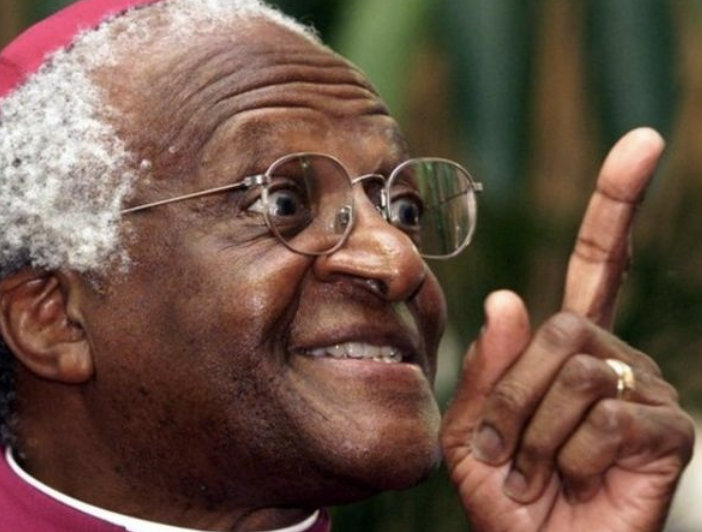

Desmond Tutu dies aged 90

Archbishop Desmond Tutu, the Nobel Prize Laureate who helped bequeath “a liberated South Africa and end apartheid in South Africa, has died aged 90.

According to Nelson Mandela, he was one of the driving forces behind the movement to end the policy of racial segregation and discrimination enforced by the white minority government against the black majority in South Africa from 1948 to 1991.

Charismatic Tutu, was a high-profile black churchman inevitably drawn into the struggle against white-minority rule but always insisted his motives were religious, not political.

Desmond Miplo Tutu born in 1931 in a small gold-mining town Transvaal, was appointed by Nelson Mandela to head South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission set up to investigate crime committed by both sides during the apartheid era. He first followed his father’s footsetps as a teacher, but abandoned, when the Bantu Education Act introducing racial segregation in schools. He then joined the church and was strongly influenced by many white clergymen in the country, especially Bishop Trevor Huddleston. He served as bishop of Lesotho from 1976-78, assistant bishop of Johannesburg and rector of a parish in Soweto, before his appointment as bishop of Johannesburg. As a dean he first began to raise his voice against injustice in South Africa and again from 1977 onwards as general secretary of the South African Council of Churches. Before the 1976 rebellion in black townships, months before the Soweto violence he first became known to white South Africans as a campaigner for reform. He coined the term Rainbow Nation to describe the ethnic mix of post-apartheid South Africa.

Desmond Tutu’s enthronement as Archbishop of Cape Town was attended by the then Archbishop of Canterbury, Dr Robert Runcie, and the widow of Martin Luther King. As head of the Anglican Church in South Africa, he continued to campaign against apartheid in March 1988, he declared “We refuse to be treated as the doormat for the government to wipe its jackboots on”.

He was never afraid to voice his opinions in April 1989, when he went to Birmingham in the UK, he criticised what he termed “two nation” Britain, and said there were too many black people in country’s prisons. He angered the Israelis when, during a Christmas pilgrimage to the Holy Land he compared black South Africans with the Arabs in the occupied West Bank and Gaza. He could not understand how people who had suffered as the Jews had, could inflict such suffering on the Palestinians.

“God is weeping” he once said, when he accused the church for allowing an obsession with homosexuality to take precedence over the fight against world poverty.

He returned to the subject of poverty when he visited Ireland in 2010. He urged Western nations to consider the effect of cuts in overseas aid in the wake of the economic downturn.