Concrete beauty towers

English Heritage has over 400 historic monuments including buildings, places from world-famous prehistoric sites to grand medieval castles and Roman forts but not British concrete buildings that seek to rehabilitate as much-maligned architectural style.

Concrete is coming back to fashion, as Denys Lasdun’s National Theatre was voted Britain’s most-hated building.

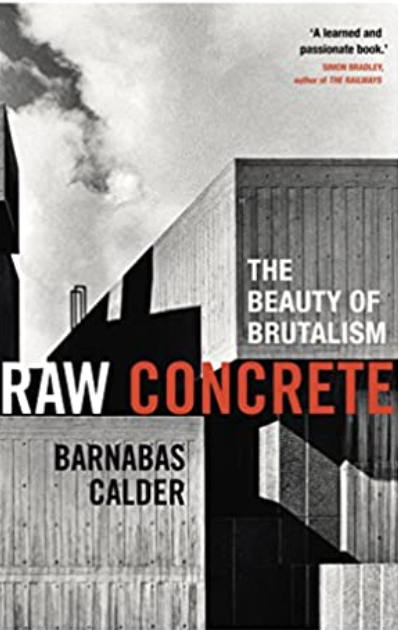

Architect and historian at Liverpool University, Barnabas Calder’s Raw Concrete gives a guide to eight of Britain’s landmark concrete buildings of the mid-20th century.

The raw concrete buildings of the 1960s constitute the greatest flowering of architecture the world has ever seen. The biggest construction boom in history promoted unprecedented technological innovation and an explosion of competitive creativity amongst architects, engineers, and concrete workers proving a brutalist style.

Raw Concrete overturns the perception of Brutalist buildings as the penny-pinching, utilitarian products of dutiful social concern. Instead of looking a little closer, uncovering the luxuriously skilled craft and daring engineering with which the best buildings of the 1960s came into being magnificent architectural visions serving clients rich and poor, radical and conservative.

Eight extraordinary buildings were made from commission to construction, and they have been vilified and loved. A tiny heritage on the remote north Scottish coast, and ending up backstage at the National Theatre, brings daily pleasure. He leads us inside his favorite buildings from Hermit’s Castle- a remote 1950s folly in northwest Scotland, built by David Scott. London’s Barbican, aesthetically perceptive (elating Goldfinger’s Trellick Tower in West London, and Owen Luder’s Trinity Square complex in Gateshead, now demolished and mourned.

As a student Calder lived in Lasdun’s 1966 New Court extension to Christ College, Cambridge – a great hillside of glistening white”. Rooms are arranged around staircases, and there is grass outside, college fellows get bigger rooms than everyone else. The difference is concrete a mix of cement, water, and gravel. At a time of the post-1945 rebuilding of an expanding welfare state and big commissions, architects had the ability to slide the constituent parts of their buildings around at will. “Architects felt no sentimental or apologetic need to disguise this thrilling process behind ill-fitting simulacra of the architecture of older, poorer, more cruelly hierarchial periods in human history”.

Raw Concrete: The Beauty of Brutalism by Barnabas Calder, Heinemann £30, 416 pages.