Calls to reveal the source of covert political donations

Like US, India’s political parties rely heavily on contributions from businesses to finance their election campaigns.

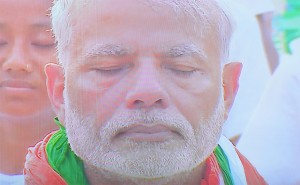

Couple years ago, Mr Narendra Modi’s government unveiled what it called as a major clean-up to purge “black money” from politics, by introducing a system of “electoral bonds” for companies and wealthy individuals to make legal and anonymous donations to political parties, to deal with India’s weak and poorly enforced laws on political donations which has ensured the precise links between businessmen and the parties they support are shielded from public scrutiny.

According to critics the scheme has only legitimised and legalised the covert corporate political contributions that were once made through clandestine cash transactions.

The bonds are promissory note purchased from the State Bank of India for donating to political parties rather than individual candidates. The parties then deposit the funds in special accounts. The SBI only knows who bought the bonds but not where they went, while only the recipients are supposed to know their benefactors’ identities. The parties must also report precisely how much money they raised through the bonds and how the funds were spent.

In 2018 alone, donors bought around £115million worth of electoral bonds, according to the results of a right to information filed by an activist based in Pune.

In the first three months of this year, electoral bonds worth about £190 million were sold, according to the same request for right of information.

There were criticism during Modi’s first prime ministerial campaign in 2014, where he did his whistle stop tour around the length and breadth of India covering over 400 election rallies in a corporate jet and two helicopters owned by Gautam Adani, a billionaire industrialist whose interests span from power, ports and other infrastructure businesses. According to rival Congress party, Modi’s use of the aircraft were free, but Mr Adani said the politician had not used them for free, but the figure Mr Modi paid was never disclosed.

The Election Commission of India (ECI) has told Supreme Court that electoral bonds, contrary to government claims, wreck transparency in political funding. The removal of cap on foreign funding, they invite foreign corporate powers to impact Indian politics according to an affidavit filed in the apex court.

India is gearing up for general elections on April 11, as relations between tycoons and politicians are opaque.