Greek Influence of both the ancient and Hellenic world on Western science

The Greek, city-states, led by Athens and Sparta, two thousand years ago laid the foundation for much of modern science, the arts, politics, and law. Historian Roderick Beaton, emeritus professor of modern Greek and Byzantine history, language and literature at King’s College London, traces history from the Bronze Age Mycenaeans who built powerful fortresses at home and strong abroad, to the dramatic Eurasian conquests of Alexander the Great, to the pious Byzantines who sought to export Christianity worldwide to today’s Greek diaspora that flourishes on five continents, and illustrates over three millennia Greek speakers produced a series of civilisations that were rooted in southeastern Europe but again and again ranged widely across the globe. The Greeks and their global impact told as never before.

Percy Bysshe Shelly’s best poems Hellas composed after the Greek war of Independence broke in 1821.The preface of the poem contains a summary in the English language of the debt that western civilisation owes to the ancient Greeks. Shelly wrote “ We are all Greeks, our laws, our literature, our religion, our arts have their root in Greece.”

The Independent Greek state emerged from the ferocious struggle against Ottoman overlordship in the 1820s. The Greek cause was in dire straits until the British, French and Russians destroyed the Ottoman fleet at the battle of Navarino in 1827 – “the last great naval battle of the age of sail”.

The Greek independence set a precedent that echoes across two centuries of Europe history up to the present age.

Beaton, in an authoritative guide to the countless ways Greek words and ideas shaped the modern world, alphabet, athletics, democracy, politics, drama, history, pandemic, physics, politics rhetoric – all from ancient Greek. Much of the Greek influence was filtered through the Roman Empire. In the first century BC, poet Horace said “Captive Greek took captivr her fierce conqueror and introduced her arts intyo rude Latium.”

Great centres of Greek civilisation such as Alexandra, Constantinople, and the southern black sea coast lie outside the modern Greek state.

After the fall of the Roman Empire in the west in the fifth century, Constantinople emerged as the capital of Greek speaking eastern empire that became known as the Byzantium.

Most Greek speakers from Mediterranean and Aegean seas to Cyprus and Anatolia, lived for the next seven centuries under the rule of foreigners – Aragonese, Catalans, Florentines, French, Genoese, Venetians, and after the fall of Constantinople in 1453, Ottomans. Athens was ruled in the 13th century by a family from Burgundy.

Ordinary Greeks were second class citizens in the Ottoman Empire, but Beaton suggests when reminding us of Spain’s expulsions of Jews and Muslims from 1492 onwards. By the 18th century the Ottoman’s relied on Phanariots, Greek speaking aristocrats, to rule the provinces of Moldavia and Wallachia, now part of Romania. In the ancient and medieval era the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople.

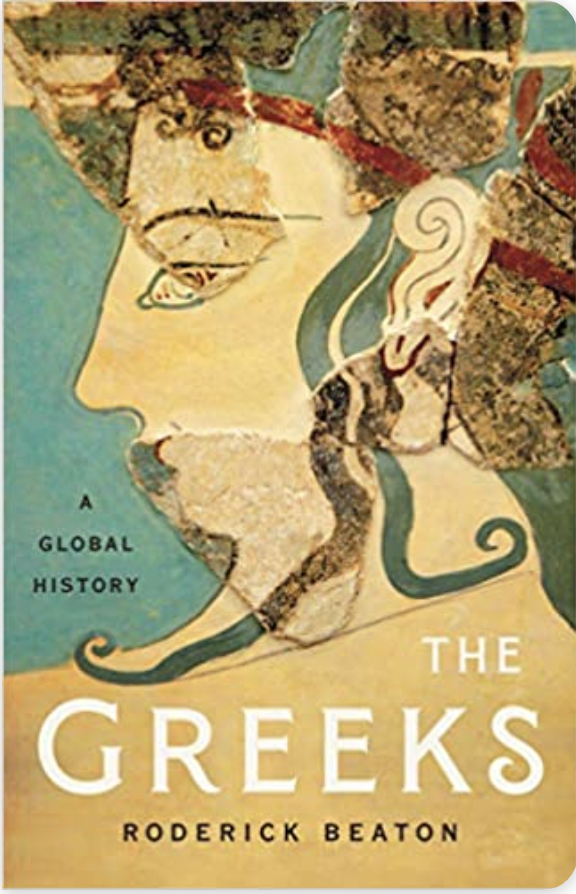

The Greek: A Global History by Roderick Beaton, Faber £25, 588 pages.