Napoleon, a botanist, and horticultural strategist

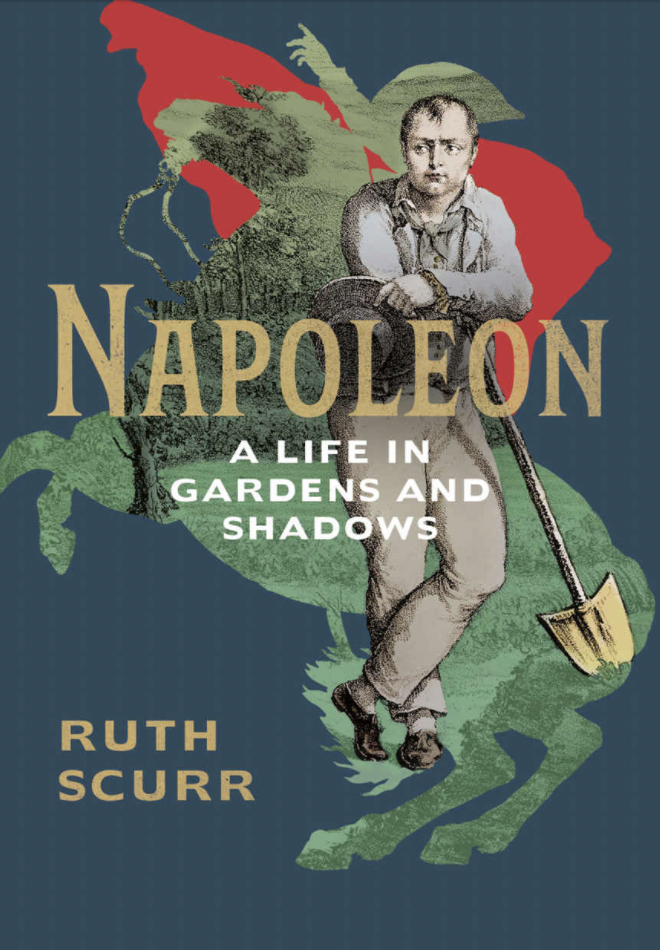

Napoleon Bonaparte ( 1769-1821), the most celebrated general in history, has always attracted eminent male writers but only a few female writers have written his biography. Ruth Scurr, a lecturer in history and politics at Cambridge University, a keen Gardner herself, who knows her pelargonium from her amaryllis is one of the most eloquent and original historians, empathetically reject the “Great Man” theory of history, instead following the dramatic injectors of Napoleon’s life though gardens, parks and forests. Gardening was Napoleon’s first and last love, offering him retreat from the manifold frustrations of war and politics. Gardens were, at the same time, a mirror image to the battlefield on which he fought, discrete settings in which terrain and weather were as important as they were in combat, but for creative rather than destructive purposes. Ruth Scurr takes us from his early days at the military school in Brienne-le-Chateau through his canny seizure of power and eventual exile. Napoleon’s story though the green spaces he cultivated, amid Corsican olive groves, ornate menageries in Paris, a lone garden plots on the island of Saint Helena with diverse cast of scientists, architects, family members, and gardeners. She also offers indelible portraits of Augustin Bon Joseph de Robespierre, the younger brother of Maximilien Robespierre who used his position to advance Napoleon’s career. Marianne Peusol, the fourteen-year-old girl manipulated into a Christmas Eve assassination attempt on Napoleon that resulted in her death, and Emmanuel, comte de Las Cases, the atlas maker to whom Napoleon dedicated his memoirs. Scurr reveals how Napoleon’s dealings with these people offer unusual and unguarded opportunities to see how he grafted a new empire onto the remnants of the ancien regime and the French Revolution.

As Emperor of “Elba”, he was brought in great state to witness the ritual catch, done, ever since antiquity, by converging netted tunnels suspended between parallel aisles of boats. When the enormous fish reached their dead end fisherman bashed them with clubs and finished them off in the bloody water with knives.

Tuna eating skinny Napoleon was allotted an imperial-size fish to haul in and administer the coup de grace. He puffed and heaved and failed to land it.

Scurr quotes a 19-year-old grenadier, the only one of 60 from his hometown of Chartres to survive the last campaigns saying “If Bonaparte had reigned longer, he would have murdered all the world, then made war with animals”.

France could afford endless campaigns without punitively impoverishing the French, was to levy crushing indemnities on the “liberated”, thus making territorial expansions self-financing. Once the machine of victory went into reverse, everything, including Napoleon himself, went pear-shaped, 1813-1814 was as bad as the years immediately before the fall of the ancien regime.

From is first min allotment at the. Military school in Brienne-le-chateau, to the Sisuphean effort to create a paradise on st Helena in the face of terminally hostile elements ( including the horrible British governor-jailer. Sir Hudson Lower), Napoleon was, at the same time, a horticultural strategist imposing classical rectangularity on unruly verdure and the porto-romantic whose dream was a carpet of violets.

The man never told a bigger lie than when he claimed, even as he was extinguishing freedom of the press, that he had established the Revolution on the principles which began it.

In1795, Napoleon in his mid-twenties had a go at writing a sentimental novel popularised by Rousseau and Bernardin de Saint-Pierre.

Napoleon: A Life Told in Gardens and Shadows by Ruth Scurr, Chatto Windus £30/Iveright $28.95, 400 pages.