Perils of Loneliness

In cities, we stand silent in buses and train carriages, ignoring each other. Online, we retreat into silos and carefully create who we interact with. In politics, we are increasingly consumed by a fear of people we’ve never met. But imagine what if strangers, long believed to be the cause of our problems, were actually the solution?

A 6pm train from Black Friars to Streatham was detained rather a long time at Herne Hill station, with other trains overtaking it from adjancent station, when all the passengers were minding their own business with pin drop silence, only occasional shifting of newspaper pages. A failure to announce the reason for the delay, a frustrated passenger put his head out and yelled at the driver “Do you want a push?” followed by loud laugher.

Modern neuroscientists believe the body’s stress response to isolation evolved to nudge us back to the protective folds of the tribe when being alone really was a death sentence. But scientists are not exactly sure how social links create health benefits although one theory holds that a release of endorphins, which also have an analgesic effects group activities, prompted by the presence of friends, boosts the immune system.

Emily Dickinson’s poem titled The Loneliness One dare not-sound” likened the horror of loneliness to being buried alive. Loneliness is a collective condition, the social, medical and economic cost of loneliness according to Vivek Murthy, a US surgeon declared it a public health crisis. Former Prime Minister Theresa May even appointed the UK’s first “minister for loneliness” followed by Japan this year.

According to a YouGov survey of the adults almost half of them reported feeling lonely at least few times a month in 2019, before the advent of the pandemic and loneliness was most prevalent among the 18-24 year-old youngsters.

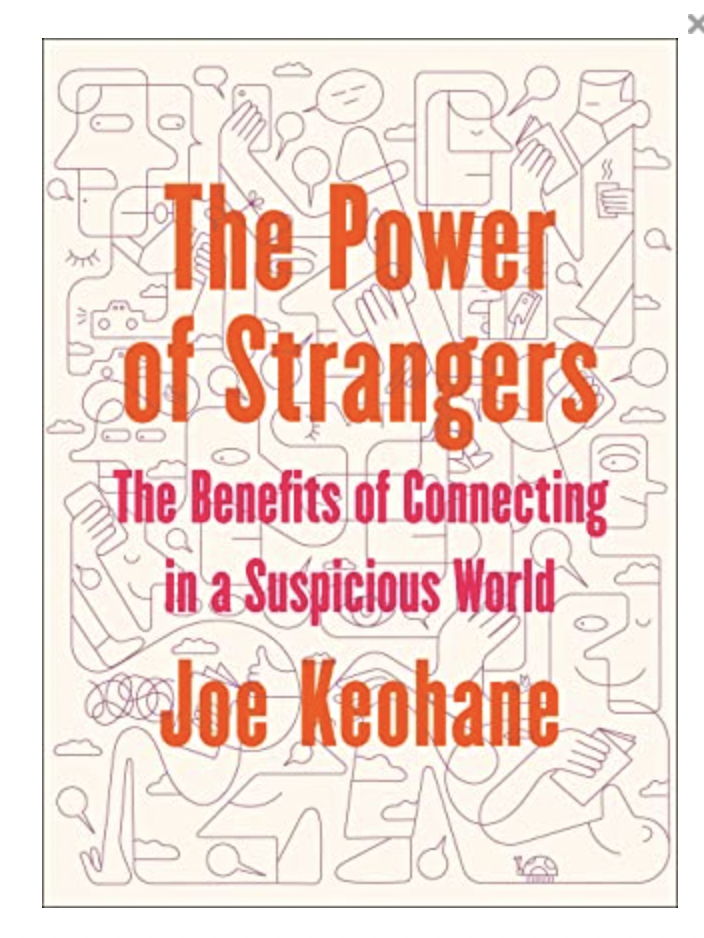

Joe Keohane investigates why we don’t talk to strangers, and what happen when we do. From enhancing empathy, happiness and cognitive development to easing loneliness and isolation, passing encounters can root us in the world, deepening our sense of belonging.

The Power of Strangers will make you reconsider how you see others, and in doing so show us how talking to strangers is not just a way to live, it’s a way to survive.

As the pandemic drove us deeper into our devices away from public spaces, we not only saw less of our friends and family but also had far fewer interactions with strangers. Journalist Joe Keohane cites recent studies in social psychology reveals that it is not only friendships that enhance well-being , even fleeting interactions in the world at large, can enhance empathy, increase happiness and deepen our sense of belonging.

Due to the potential risk associated with strangers not least pathogens, our primal instinct is one of fear. We also tend to overestimate the risk of rejection.

People are happier on days whey they have had weak-tie interactions, with one study showing that those who talked to their baristas while ordering coffee reported a stronger sense of belonging and an improve mood.

We miss out on valuable exchanges when we prioritise on efficiency over connection in pursuit of frictionless existence – a trend accelerated by contact-free services. “ Rendered invisible by technology, the legions of strangers who serve our needs” are “condemned to a permanent strangehood.”

Keohane advocates breaking the script of small talk for more authentic conversations. “How are you” rarely elicits a genuine response.

“How was your day been” , he finds one develops what Keohane calls “strange mojo” – an openness and confidence that invites interaction.

Fellow Xenophiles agree that “when you get into the habit of talking to people, people just start talking to you.

The demographics and cultural shifts over the past century that have led to loneliness are irreversible.

The Power of Strangers: The Benefits of Connecting in a suspicious world by Joe Keohane, Viking £16.99/Random House £28, 353 pages.