Resistance to abolition of slavlery

The English Heritage unveiled blue plaque on the wall of Schomberg House on Pall Mall, London to commemorate the residence of Quobna Ottonah Cugoano, the author and campaigner in 1787 wrote one of the first exposes by an African of slave trading, criticising continued tolerance of horrors of the slave trade by the British Government and public, who is consuming the products of slavery –from the breakfast table to tavern – made it profitable.

For two hundred years, the abolition of slavery in Britain has been a cause for self-congratulation- but no longer.

In 1807, although the British Parliament outlawed the slave trade in the British Empire, for the next quarter of a century, despite heroic and bloody rebellions, more than 700, 000 people in the British colonies remained enslaved. When a renewed abolitionist campaign was mounted, making slave ownership the defining political and moral issue of the day, emancipation was fiercely resisted by the powerful “West India Interest”, supported by nearly every leading figure of the British establishment including Canning, Peel, and Gladstone. Their interest ensured that slavery survived until 1833 and that when abolition came at last, compensation worth billions in today’s money was given not to the enslaved but to the slaveholders, entrenching the power of their families to shape modern Britain to this day.

Cugoano, a former slave himself, said “ seeing my miserable companions and countrymen in this pitiful distress and horrible situation, with all the British baseness and barbarity attending it, could not but fill my little mind with horror and indignation”.

Despite all this slavery remained central to Britain’s trading activities, as the country was slow to acknowledge the heinous realities of slavery, and pressure for change met with outright hostility. To stall reform and prevent emancipation by putting pressure on parliament and influencing public opinion the London Society of West India Planters and Merchants, supported by the Atlantic “outports” ( Liverpool, Bristol, and Glasgow). A literary committee was established with an annual budget of £20, 000 ( £.18m today) to protect “West India colonies through the press” as funding came from sixpences (“preslavery rent) on Britain’s imported casks of sugar, coffee, and rum.

Michael Taylor asks who, what, and where the necessary great obstacles to reform and how these were overcome.

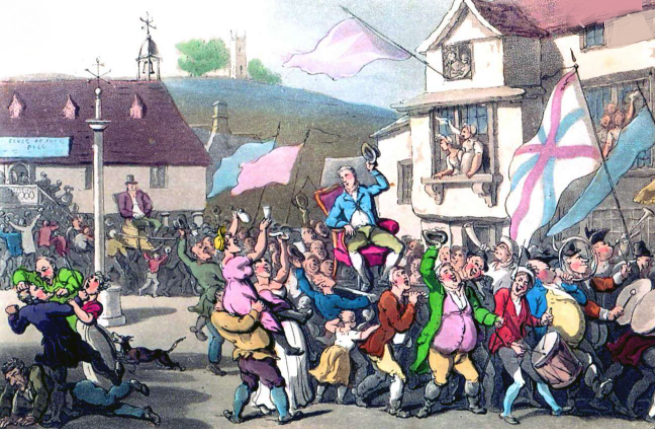

He highlights the 1832 general election which in the wake of the Great Reform Act that extended the franchise, produced the first parliament in favour of abolition.

The slaveholders, not the enslaved would be compensated and adult enslaved people would serve mostly unpaid apprenticeships for up to 12 years, using any earnings to buy their freedom. Following negotiations, apprenticeships fell to seven years, and compensation to slaveholders was capped at £20 million.

Thus British colonial slavery was duly abolished and after revelations of cruelty, Parliament in 1838 forbade apprenticeships.

Banking syndicates led by Rothschilds, Barings, and the economist David Ricardo offered rescue package to arrange loans, as by mid-1835 as much as 45, 000 British slaveholders had claimed compensation, the national debt finally paid off by the UK Treasury in 2015.

The Interest: How the British Establishment Resisted the Abolition by Michael Taylor, Bodley Head £20, 400 pages.