Rise of Warner Bros Records

Amid the world of digitally streamed music, there will never be another record company quite like Warner Bros Records, that successfully signs and promotes acts, rather in terms of an enterprise that populates the culture of the moment, from Hendrix to Fleetwood Mac to the Eagle to Van Halen to Tom Petty to the Red Hot Chilli Peppers to R.E.M to Madonna to Prince, introducing a mass audience to the cream of current innovation and becoming g more commercial and artistic titan.

One of the most compelling figures in the Warner Bros story are the sagacious Mo Ostin and the crew of hippies, eccentrics and enlightened executive he brought into the company.

Ostin transformed the out of touch company, revolutionised the industry, and within a few years created the most successful record label in American music history.

One day 1967, the newly-tapped label manager Mo Ostin called his team together to share his grand strategy. Stop trying to make hit records. “Let’s just make good records, and we’ll turn those into hits” a stance that chimed with the countercultural ethos of the 1960s, when Warner not only built its reputation, but also carried on into later decades as the label was home to the likes of REM and the Red Hot Chilli Peppers. Warner stood out in its counterintuitive approach to acquisition, marketing and management.

In 1958, spurred by some film music successes, Warner Bros decided to expand out from its home base in movies, Purchasing an albums worth of sessions by guitarist Alvino Rey, Warner then needed a title for it. Record buyers seemed equally bemused by an eccentric debut, which duly flopped. The company’s first successes were a Grammy winning comedy album The Button-Down Mind of Bob Newhart and the arrival of entertainment royalty in the form of Frank Sinatra, with his own label Reprise Records, headed by Ostin. A 1962 comedy parody record My son, the folk singer provided an unexpected stepping stone to the emerging counterculture. Mike Maitland, Warner Vice President looking for folk music approached Bob Dylan’s manager to see what else he had and ended up signing Peter, Paul and Mary an emerging trio who captured the hearts of young record buyers. Sensing the gold rush in San Francisco, Warner bought Autumn Records, headed by disc jockey Tom Donahue, who alerted them to warlocks, a band who were doing something totally different. When Warner caught their act they had changed their name to the Grateful Dead and ushered in the golden and distinctive period of Warner.

Ostin ushered a counterintuitive model that matched the counterculture. His team recruited outsider artists and gave them free rein, while respecting out-of-date methods of advertising promotion and distribution by taking into account the upstarts’ experiences paid off to the tune of hundreds of legendary hit albums.

Warner Bros’s distinction went beyond the marquee names on its expansive roster of talents.

Warner Bros embraced novel ways to promote records and to sell the unsellable to the world. They would post you a bag of Laurel Canyon dirt to promote Joni Mitchell or sell you two-LP samplers of assorted Warner artists for $2 in the hope you’d buy their full length ones for the regular price.

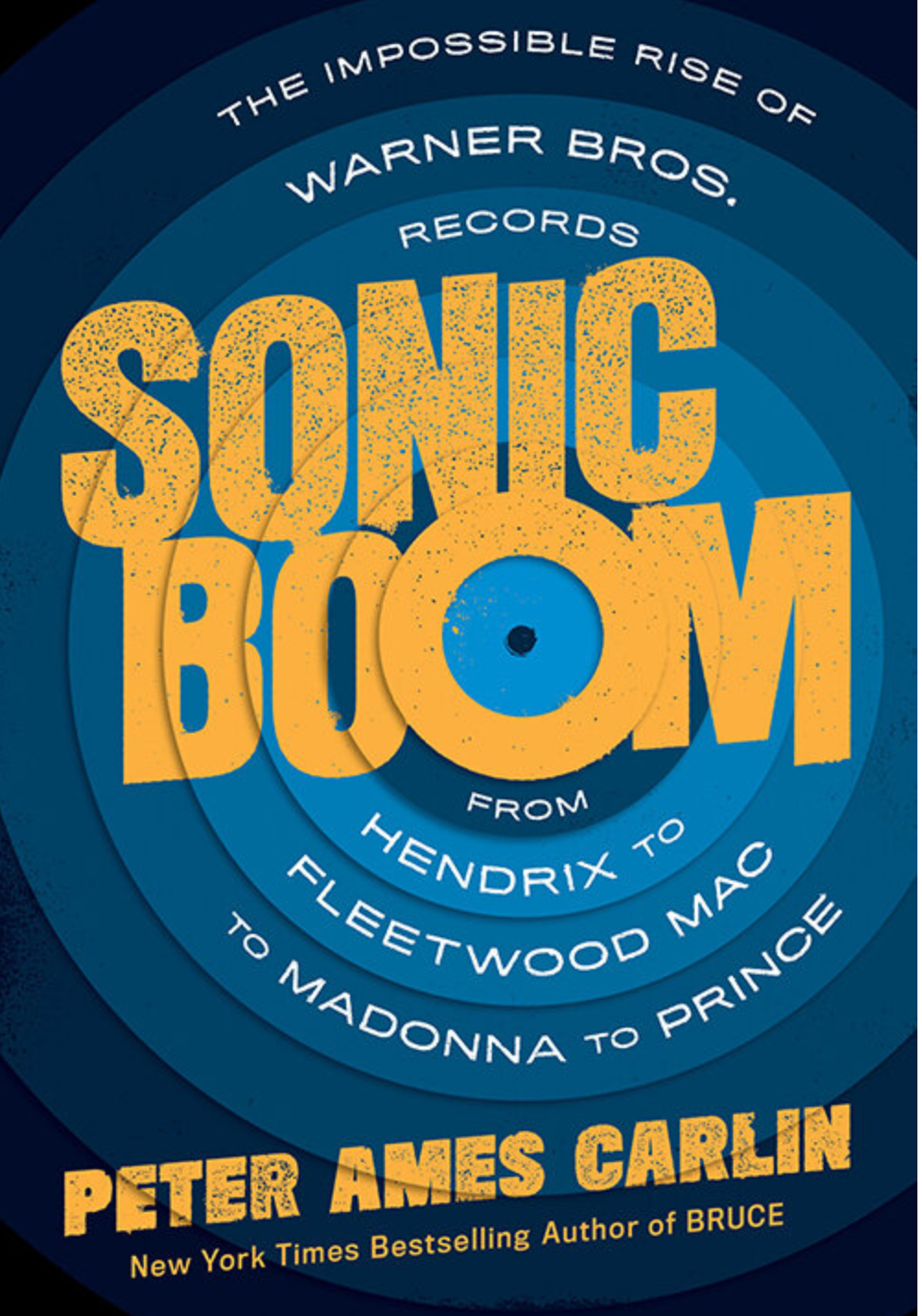

Warner Bros Record’s rise, triumph and fall is explained in Sonic Boom with unharnessed creativity against profit-obsessed standards of modern corporate culture and a reminder that the numbers on a profit-and-loss statement never tell the whole story.

The Warner Bros Records and its subsidiary labels read like a list of Rock and Roll hall of Fame inductees.

Sonic Boom: The Impossible Rise of Warner Bros. Records, from Hendrix to Fleetwood Mac to Madonna to Prince by Peter Ames Carlin, Henry Bolt & Co, $29.99, 288 pages.