Scent of iconic perfumers

The turmoil of the Russian Revolution brought the formula for a fragrance, which had been created for the 300th anniversary of the Romanovs, to France.

German academic specialising in Russian history, Karl Schlögel writes “In the beginning was a scent – a somewhat sweet, heavy aroma” that once filled the air on festive occasions in Moscow and unravels the interconnected histories of two of the world’s most celebrated perfumes. He decides to research the story of Krasnaya Moskva (Red Moscow), a popular Soviet perfume. In the glittering world of perfume he seems to have alighted one of the remarkable pairings in the early 20th century history -Parisian haute couture juxtaposed with flint-faced communist officialdom. In Tsarist Russia, two French perfumers -Ernest Beaux and Auguste Michel -developed related fragrances honouring Catherine the Great for the 300th anniversary of the Romanov dynasty. During the Russian Revolution and Civil War, Beaux fled Russia and took the formula for his perfume with him to France, where he sought to adapt it to his new French circumstances. He presented Coco Chanel with a series of ten fragrance samples in his laboratory and, after smelling each, she chose number five- the scent that would later go by the name Chanel No.5.

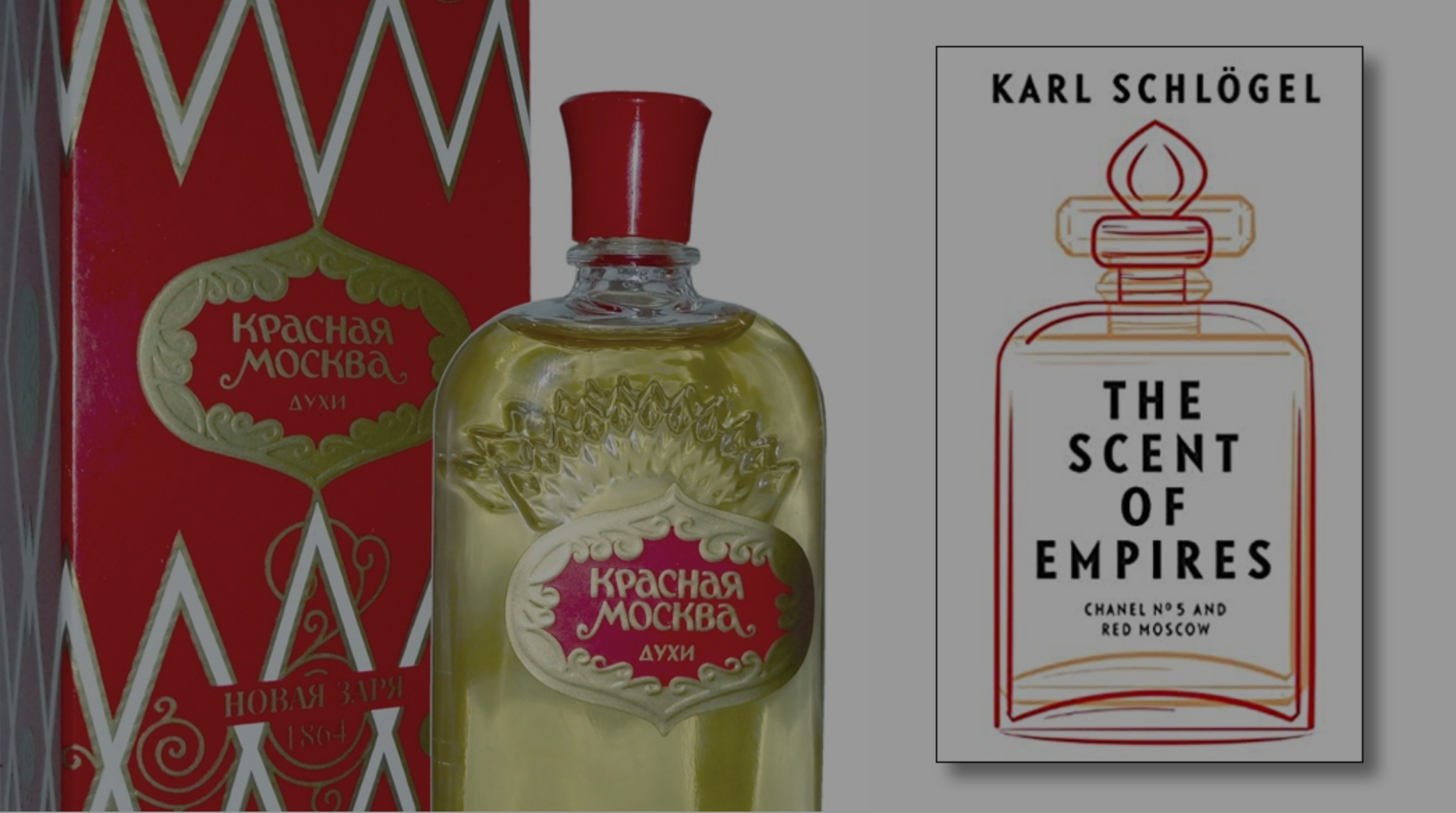

The Scent of Empires, translated by Jessica Spengler, reveals divergent fates of the individuals involved in creating Chanel No.5 and Red Moscow created by French perfumers who had studied under the same master perfumer, worked in Tsarist Russia, Chanel No.5 by Ernest Beaux who fled to France in 1919 and Red Moscow by Augusta Michel, who remained in Russia, after the revolution.

Overlapping employer meant that Michel would have the access to the formula of Beaux’s precedent creation, Le Bouquet de Napoleon.

Chanel No.5 which celebrates this year the centenary of its release was the quintessential essence of it era, balancing jasmine and rose with the freshness of aldehydes, synthetic molecules that dissipate quickly boosting the essence of fragrance.

Chanel No.5’s creation myth imagines a lab assistant accidently overdoing the aldehydes, Schlögel argues that the formula was a variation on Le Bouquet de Catherine.

Michel had developed his own homage to the empress, Le Bouquet Favori del’ Imperatrice also launched in 1913, while France embarked on Led Annees folles .

Chanel maintained her residence at the Ritz during the occupation of Paris settled in Switzerland after the second world war to avoid criminal charges of collaboration, Zhemchuzhina was exiled for five years during Stalin’s anti-Semitic campaigns despite being a staunch Stalinist.

Beaux continued to produce perfumes and lived until the age of 79, Michel disappeared without a trace in 1937, likely victim of the Great Purge, as those with foreign surnames were vulnerable to accusation of espionage.

Auguste Michel of Soviet Russia, used his original fragrance to create Red Moscow for the tenth anniversary of the Revolution. Piecing together the intertwined history of two famous perfumes, which shared a common origin, Schlogel tells a surprising story of power, intrigue and betrayal amid turbulent events and high politics in twentieth-century Europe.

The Scent of Empires: Chanel No 5 and Red Moscow by Karl Schiögel, translated by Jessica Spengler, Polity, £20, 220 pages.