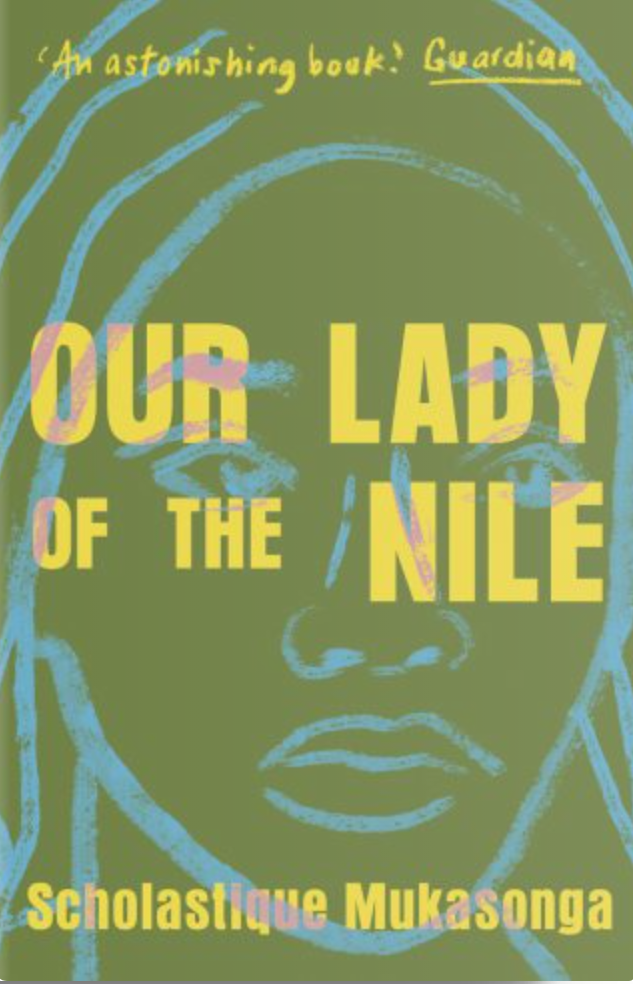

Sinister story set at an elite girls boarding school

Fifteen years prior to the 1994 Rwandan genocide and a quota permits only two Tutsi students for every twenty pupils.

French Rwandan writer Mukasonga reveals the prelude to the Rwandan genocide and unfolds behind the closed doors of the elite school for the girls in the interminable rainy season.

Nothing at Our Lady of the Nile is as it seems: neither the statue of the “black” Virgin Mary placed at the source of the river, nor the Christian names the girls are given in place of their Rwandan ones, nor even the purported function of the institution. The young ladies here are daughters of high-ranking government officials and businessmen, their weddings are matters of political alliances, and the school is a training ground for their adult lives.

“Come are the days when beauty was all that mattered, thanks to their daughters, these families will grow wealthy, the power of their clans will be strengthened, and the influence of their lineage will spread far and wide ”, the narrator tells us.

Rwanda’s interpretation of the Ethnological myth, and racial and ethnic differences by European colonisers that has determined so much of the country’s turbulent history.

The elite school run by Christian missionaries in Kigali in the 1970s, depicts a society hurtling towards violence and genocide.

The pupils of Our Lady of the Nile mimic the politics of their fathers as their loyalties and allegiances shift. “There were two races in Rwanda. The Whites had said so they were the ones who had discovered it. They’d written about it, in their books. Experts came from miles around and measure all the skulls.

There are Hutu girls like Gloriosa, the school’s Hutu queen bee tries on her parents’ preconceptions and prejudices, Immaculee, Goretti, Modesta, and the Tutsi girls like Veronica and Virginia whose admission is regulated by strict ethnic quotas. The Tutsi girls are exoticised in the imagination of their white teachers and Monsieur de Fontenaille, a former colonist and owner of coffee plantation next to the school and reviled by their Hutu-majority classmates.

Gloriosa taunts “ Your supposed beauty will bring your misfortune”.

Mukasonga’s young boarders are proud, sometimes shy often funny. They swap skin -whitening creams, they argue over the best way to cook bananas as they complain about school meals ( Everything the whites eat come out of cans”), they cut strips of fabric in sewing class which becomes sanitary pads once the girls are initiated into the “mysteries of a woman’s cycles”.

Friendships, desires, hatred political fights, incitation to racial violence, persecutions are all explored as the school becomes a fascinating existential microcosm of the true 1970s Rwanda.

“There is no better lycee than Our Lady of the Nile, nor is there any higher, twenty-five hundred meters, the white teachers proudly proclaim.” Parent send their daughters to Our Lady of the Nile to be moulded into respectable citizens and to protect them from the dangers of the outside world. The young ladies are expected to learn, eat, and live together, presided over by the colonial white nuns.

Rwanda is a country divided and a society hurtling towards horror, amid growing up young women’s dreams and ambition and prejudices as their country fall apart and our inability or refusal to protect children from history.

Our Lady of the Nile by Scholastique Mukasonga, Translated by Melanie Mauthner, Daunt Books, £9.99, 224 pages.