West’s failure to understand Afghanistan and lost peace

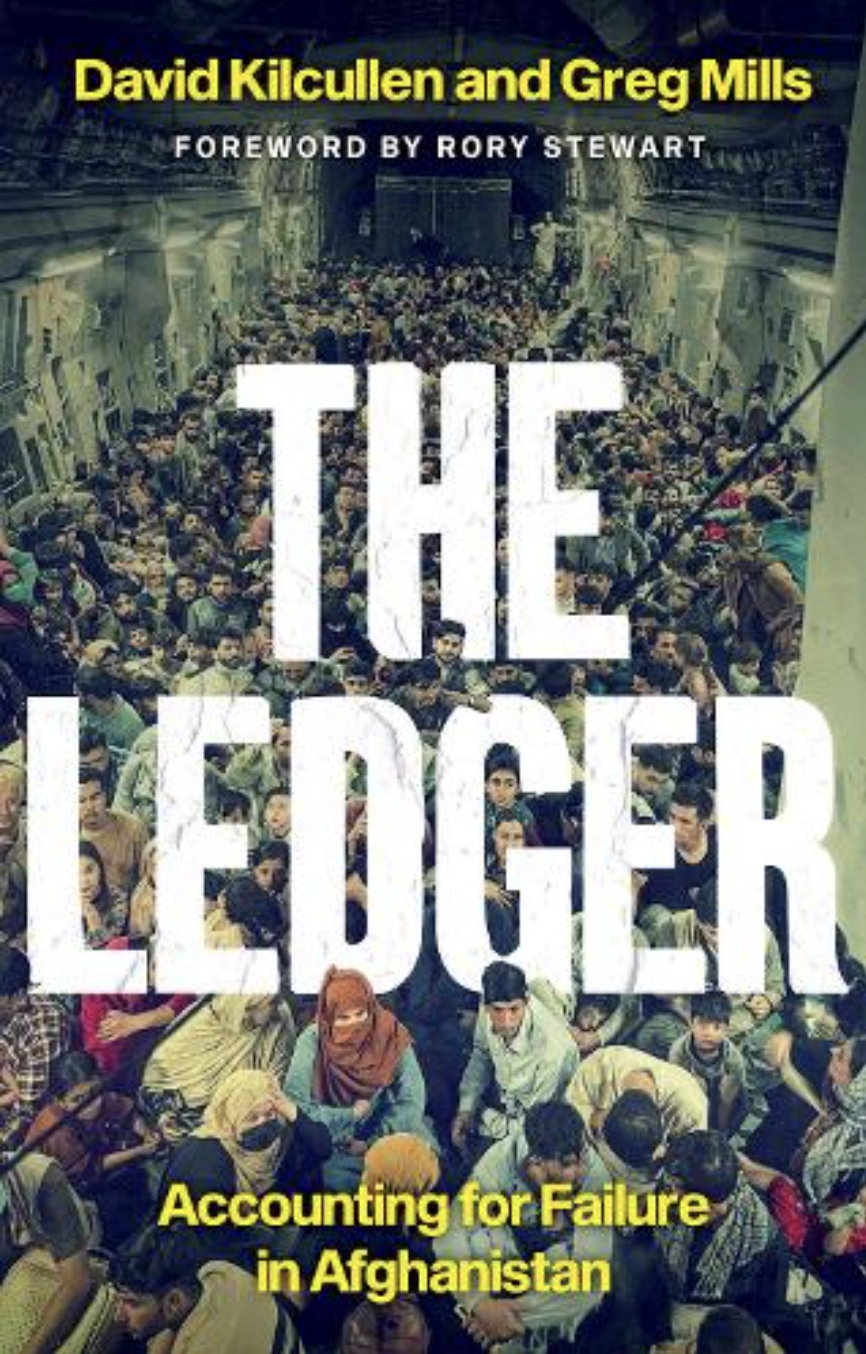

“The Ledger: Accounting for Failure in Afghanistan” assess the West’s similarly failed approach to Afghanistan in military, diplomatic, political and developmental terms and reveals the west’s failure to understand Afghanistan and the ties that bind Afghanistan, and its people underpins the west’s 20-year struggle there.

Building on record of the past starts from the first engagement in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks, as the authors trace the list of opportunities and failures that end in the US’s overnight departure from Afghanistan this summer.

“ These things happened. They were glorious and they change the world”. Said Charles Wilson of America’s role backing the anti-Soviet mujahideen, “ And then we fucked up the endgame”, with no support for Afghanistan after that war, the vacuum was filled by the Taliban and bin Laden.

Afghanistan appears to be a land divided by extreme contrasts, prosperous districts of Kabul and the austere earth-built compounds of Helmand province, only few hundred miles apart could be different from the past, spanned by relationships often invisible for foreigners.

In 2001, Lakhdar Brahimi, UN special envoy to Afghanistan, described the failure to grasp the nature of Afghan communal and tribal relationship as the West’s original sin and defined suffused all that was to follow.

After entering Afghanistan and displacing the Taliban regime, the western coalition excluded the Talibs from power and politics. The return of the exiled King Mohammed Zahir Shah to the throne was also rejected, resulting many Pashtuns the largest ethnic group in Afghanistan who had been part of the patch work regime known as the Taliban never saw their future in the western-backed regime, resistance inevitable.

Donald Rumsfeld, US defence secretary, flatly refused Karzai’s request to give Taliban leader Mullah Omar a place in his new nation, a costly mistake which meant we missed the greatest moment of leverage over the former regime and set us on an impossible course: the military annihilation of the group that was more a culture than a corps, which gave Nato a political problem that military force could not solve.

The ledger cite the advice that former Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev gave to the Kabul leaders in the 1980s, “Widen your social base, Pursue a dialogue with the tribes.” Which was never followed by Nato’s International Security Assistance, although Britain’s David Richard and America’s John Nicholson were exceptions.

The old men drinking green tea who knew every road, every well, every decision and every appointment was political with landmines waiting to go off, tales of disputes begun decades even centuries earlier. Development-workers saw spending targets and auditors wanted outputs, these elders felt shifts in power and knew the stakes and the risk that change brought.

This was the society that we dreamt of reforming, we didn’t suffer the constraints of self-doubt or popular accountability. We were able to compound our errors and tear the scabs from old wounds without feeling them bleed. We were also able to educate girls, employ women, engage doctors, and rebuild highways. The extension of the writ of government across Kandahar as the spread of corruption, not governance. They list request of the people – employment and electricity – and contrast them with the aid professionals were determined to offer education and irrigation.

Mills, a South African writer about state failure, and Kllcullen, a former Australian soldier and one-time adviser to the US national security cabal, have gathered evidence and anecdotes to tell the story of Afghanistan adventure many of us lived.

The authors were travelling along dangerous roads in an attempt to understand local highway tax system to the final days when Mills was in the Presidential palace before President Ashraf Ghani who was more interested in academic solutions to management challenges than facing the horde advancing on the capital, abandoned it for exile ignominy.

When the leadership failed, we pretended Afghanistan was a new Vietnam, and in pretending, made it so.

The failure to bring peace to Afghanistan after 9/11, as the signs of collapse were conveniently ignored in favour of political narratives of progress and success. For Afghans, the war and its geopolitical effects are not over because NATO is gone. Afghanistan remains globally connected through digital communications and networks .

The painful legacy of our decisions is visible in Afghanistan today and in the memories of veterans and can also be seen around the world.

The Ledger: Accounting for Failure in Afghanistan by David Kllcullen and Greg Mills, Hurst £14.99, 368 pages.