Cloth merchant graduating to investment and commercial bank

Private investment firm Brown Brothers Harriman, is neither a Rothschild, a JP Morgan nor a Goldman Sachs. In Inside Money, acclaimed historian, commentator, and former Financial executive Zachary Karabell, offers the first full and frank look inside the institution against the backdrop of American history and explores Brown Brothers Harriman’s central role in the story of American wealth and its rise to global power. Throughout the nineteenth century when America was convulsed by a devastating financial panic essentially every twenty years, Brown Brothers quietly went from strength to strength, propping up the U.S. financial system at crucial moments and catalysing successive booms, from the cotton trade and the steamship to the railroad, essentially managing the unwelcome attention that plagued some of its competitors.

By twentieth century, the firm took over U.S economy. To the Brown family, the virtue of their dealings was a given; their form of muscular Protestantism, forged on the playing fields of Groton and Yale, wa the acme of civilization, and it was their duty to import that civilization ot the world. When the Great Depression arrived Brown Brothers ensured their strength by merging with Averell Harriman’s investment bank to form Brown Brothers Harriman, the die was cast for the role the firm would play on the global stage during World War II and thereafter, as its partners served at the highest levels of government to shape the international system that defines the world to this day.

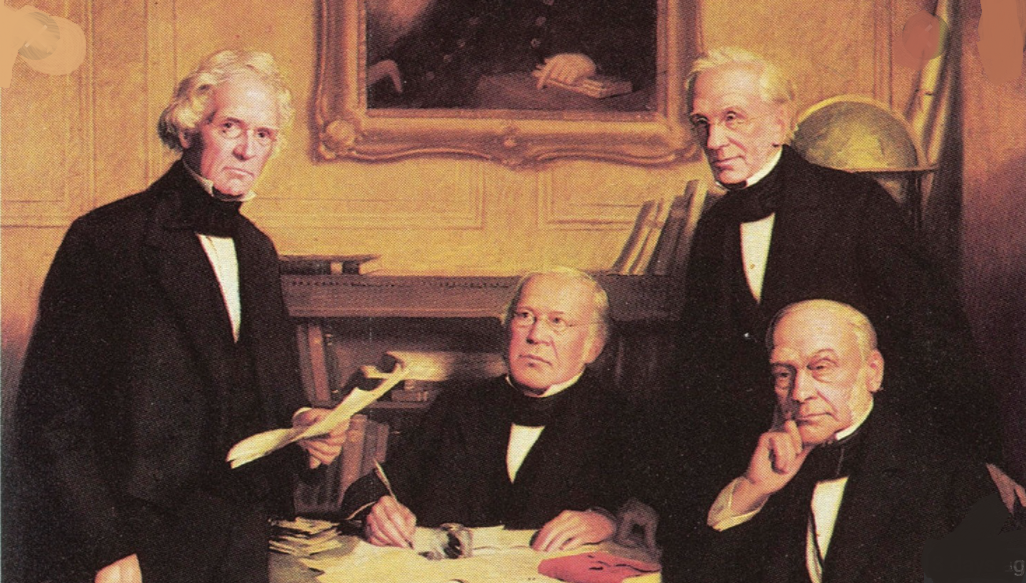

The Irish immigrant Alexander Brown and his sons, who established the firm in the early 1800s, were men of influence, but were committed to professional discretion and Christian humbleness.

In Inside Money, Karabell has created an X-ray of American power – financial, political, cultural – as Brown Brothers Harriman remains a private partnership and a beacon of sustainable capitalism, having forgone a heady speculative upsides of the past three decades but also having avoided any role I the devastating downsides. The firm is no longer in the command capsule of American economy,

Even larger public companies, answerable only to the market and fixed on profit maximisation, dominate finance now.

Brown Brothers began as a Baltimore cloth merchant, evolved into a trade finance house, then an investment bank, next a commercial bank, before finally before becoming a private partnership operating primary in the dull but crucial custody banking sector, – the plumbing as it were, of asset and investment ownership.

Brown Brothers played an important role in American economic history, from railroad boom to the convulsion of the great depression.

The firm took to heart the advice its patriarch gave to his four noys: “Shoemaker, stick to thy last”.

Focus on what you are good at, do it right, and keep quiet about it. The good advice mattered when Brown Brothers came to dominate the risky transatlantic trade finance business – which it entered because of the necessity of underwriting cotton shipments to Britain on behalf of farmers in the American South. In the early 19th century the Brown Brother’s letter of credit became as close to a universally accepted commercial currency as American had, because of the partner’s deserved reputation for risk management. The Brown Brothers were picky about who they did business with and never bet all on a single venture.

The partners early business was rooted in slavery, as the business took a bailout loan from the Bank of England, when it faced a run during the panic of 1837, its deep integration with transatlantic commerce made it too big to fall.

The bank completely dominated the finances of Nicaragua in the 1910s, in partnership with the US State Department, is typical case economic imperialism.

It controlled Nicaragua’s national bank localed in Connecticut , its currency, and its rail system, all but directly managing its economy.

During depression Brown Brothers received by merging with the investment bank run by Averell Harriman, who had inherited a vast fortune form his railroad baron father.

The firm’s reputation for competence and influence grew steadily through it all, in 1940s, Harriman and another partner, Bob Lovett. Were trapped for some of the most important civilian roles in the war and in the years that followed. Ultimately they became secretaries of commerce and defence, respectively.

Both men displayed exceptional competence as part of tight knit wasp elite that dominated the war’s industrial and diplomatic fronts.

Although both men were less useful during the cold war but contributed to the disaster in Vietnam.

Another partner Prescott Bush, paralysed his connections into a Senate seat, with which he did approximately nothing. But his son and grandson became presidents.

Brown Brothers Harriman began to fade in 1970s, partly because of flagging energies, and partly because it remaine a small, risk averse partnership while high finance was becoming a game of speed, scale and aggression.

Brown Brother’s were forced to split by the Glass Steagall regulations in the 1930s and its investment bank spinoff, Harriman Ripley ended up as Drexel Burnham Lambert, where Michael Milkan began the Junk Bond revolution, made a fortune and landed up in jail. As other Wall Street banks went public and grew vast , Brown Brothers continued in it genteel fashion.

Karabell thinks we would live in a more stable world if more companies practised this form of “sustainable capitalism”, where bankers risked their own capital, not that of shareholders and where service, not scale is the main goal.

The prudence, discretion and moderation that demand Brown Brothers is reflected in the values of the business community it served and America as a whole. As those values have lost their importance, the banking industry has changed.

Inside Money: Brown Brothers Harriman and the American Way of Power by Zachary Karabell, Penguin Press $30, 448 pages.