Emperor divorced from reality and used to bending the world to his imagination

Napoleon III, nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte, who ruled as president of France from 1848 to 1852, then as emperor until 1870, when his regime collapsed after a crushing military defeat at the hands of Prussia. In the second half of the 20th century, Napoleon’s reputation underwent a modest rehabilitation, as he won praise of France’s economic and social progress during the Second Empire. He was credited with notable foreign policy success in the Crimean war, in promoting Italian unification and in expanding France’s overseas Empire. He was seen as the exponent of modernising, strongman rule founded on dynastic myth and the conservative political instincts of a mass electorate. Napoleon was responsible for one of the most reckless military and political adventures of the 19th century French history.

His attempt in the 1860s to establish a monarchy in Mexico under Maximilian, the Habsburg archduke who was the brother of Franz Joseph, emperor of Austria.

If Napoleon is the villain of Shawcross’s The Last Emperor of Mexico, Maximilian is the anti-hero – a basically decent, introspective man who, until the emperor lured him into acting as the frontman of France’s schemes in the New World, seemed to be marked out for a lifetime of leisured royal aimlessness in central Europe.

He was encouraged in the delusion that Mexico would welcome a Habsburg monarch by his wife Charlotte, better known as Carlota, daughter of King Leopold of the Belgians. Carlota was serious, determined and fiercely ambitious – as she believed that she was destined to carry out God’s work.

He saw in Mexico a chance to draw a line against US expansionism and to create an empire on the cheap.

The outbreak of American civil war in 1861 gave Napoleon the opportunity to intervene in Mexico. A country torn by instability since independence in 1821, Mexico had lost vast tracts of territory to the US, in the war of 1846-48. He created a fabulously wealthy, informal empire on the cheap for France heaped costs of its occupation on the overstretched Mexican treasury. The US, convulsed by its domestic troubles, would be unable to stop him.

The adventure was riddled with contradictions from the start. Maximilian dreamt of ruling in a vaguely liberal, enlightened way, but most Mexican supporters of his regime were reactionaries to the core. Maximilian did not even set foot in Mexico until May 1864, more than two years later after the arrival of the first French troops. Maximilian , his Mexican allies and the French never succeeded in establishing control beyond Mexico City, a corridor of land connection the capital to the port of Veracruz, and a few other towns.

He proclaimed reforms such as the abolition of dent peonage and corporal punishment, and published decrees in Nahuati, the language of the Aztecs, for the first time in Independent Mexico’s history. His authority over the country was so limited that his reforms existed mostly on paper. “Nothing serious is done. Decrees are published every day, but none of them are executed, wrote the French envoy Alphonse Dano.

By 1865, Union forces had defeated the Confederates in the American civil war, and the writing was on the wall for Maximilian’s illusory empire. The US government warned Napoleon in no uncertain terms to end his mischief-making in Mexico. Napoleon duly pulled the rug from under Maximilian and withdrew France’s forces, Maximilian lamented: ”It seems to me impossible that the wisest monarch of the century and the most powerful nation in the world should give in to the Yankees in this somewhat undignified way”.

The self-styled emperor met an ignorable end, captured by forces loyal to Benito Juarez, Mexico’s legitimate president, he was shot by firing squad in June 1867. Maximilian was “ a man divorced from reality, a man used to bending the world to his imagination”.

Maximilian walked into a bloody guerrilla war and with a headful of impractical ideals and a penchant for pomp and butterflies the so-called new emperor was singularly unequipped for the task. The ensuing saga would feature the great world leaders of the day, popes, bandits and queens, intrigue, conspiracy and cut-throat statecraft, as Mexico became the pivotal battleground in the global balance of power, between Old Europe and the burgeoning force of the New World: American Imperialism.

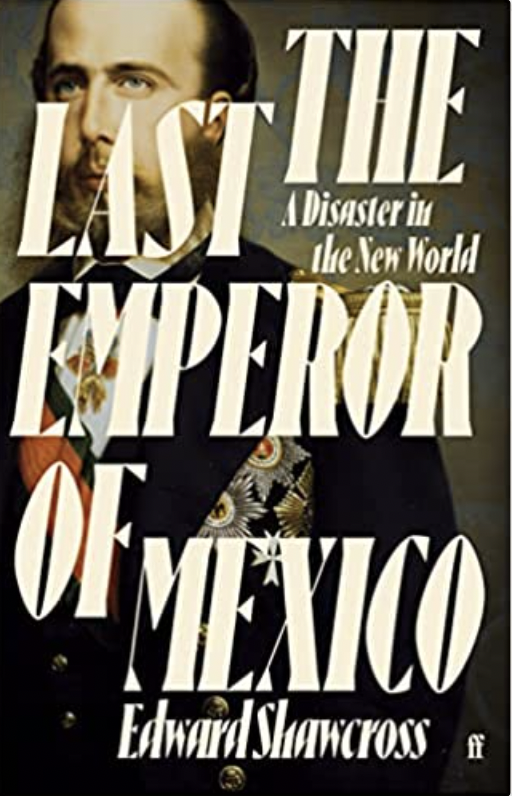

The Last Emperor of Mexico: A Disaster in the New World by Edward Shawcross, Faber & Faber £20/ Basic Books $30, 324 pages.