Greed is bad

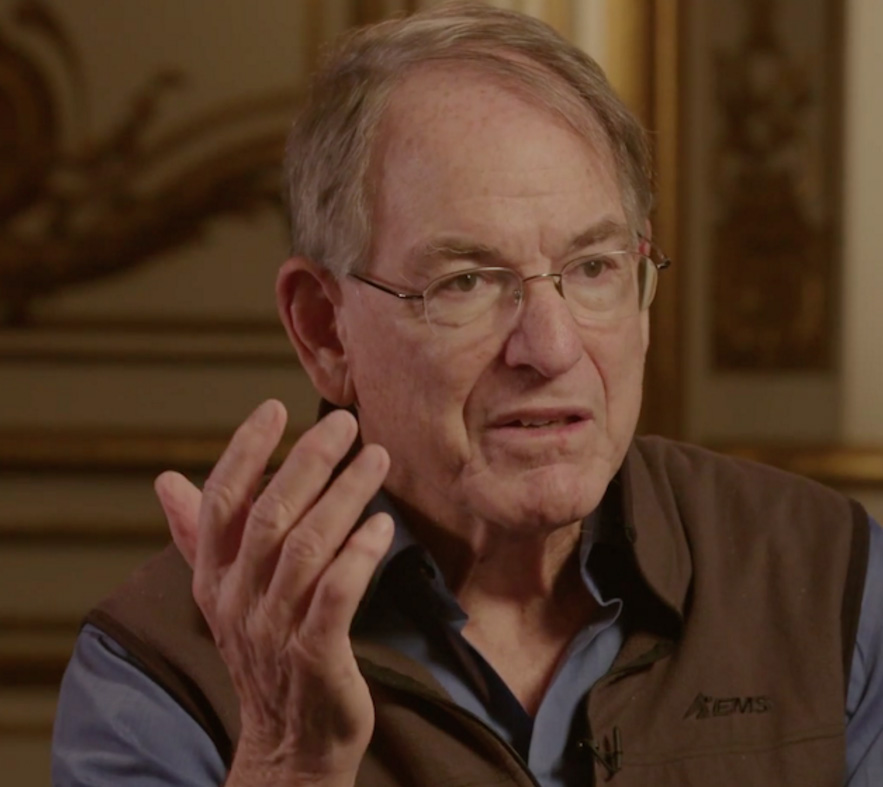

Samuel Bowles an economist at the Santa Fe Institute, makes the case that appeals made to our self-interest can undercut instinctive moral impulses, and that when these impulses are weakened , crucial institutions work sub-optimally and power of greed triumphs.

Fifteen years ago the Boston Fire Department ended its policy of unlimited sick days, hoping to curb the flu outbreaks that seemed to happen on Mondays and Fridays. Fire fighters taking more than 15 sick days would have their pay docked. The following year, number of sick days taken more than doubled, and sick days around the year-end holiday increased by an order of magnitude. The change of sick day policy replaced a relationship that respected the honour of the firefighters with one that put price on their obedience. It became something they could buy their way as many decided it is a price worth paying. This according to Bowles is “crowding out of social preferences”. The idea that markets are simply products of the interplay of selfish impulses. Mangers wants to know how the crowding threatens business productivity. But everyone who has worked in a team knows that group success depends on team members assisting one another, even in the absence of individual reward. The idea is quite prominent in white water rafting where it takes the entire team helping each other to survive.

Bowles calls on a long tradition of skepticism about the power of self-interest that reaches back as far as Aristotle and passing through Rousseau, takes its contemporary form with thinkers such as Kenneth Arrow and Albert Hirschman.

The main insight is that market structure or contract are not that perfect so that it can eliminate all opportunities for bad actors to take unfair advantage fo the credulous. There will always be opportunities to cheat. So with out good will and trust, the mutual benefit of trade and co-operation will never be realised. Each party will be too suspicious of the other to make the first move. Prices crowd out goodwill because they never are incentives.

Bowles give example of his children who, when offered to pay for doing household chores as a supplement to their allowances, stopped doing chores altogether. Their moral obligation to help around the house had been supplanted.

Individuals often reject incentives that treat them as commodities “When people engage in trade, produce goods and services. Save and invest vote and advocate policies. According to Bowles “they are attempting not only to get things but also to be someone, both in their own eyes and in the eyes of others”.

No one wants to be just a cog in the system of rewards and punishments.

The Moral economy: Why Good Incentives are No substitute for Good Citizens by Samuel Bowles. Yale University Press £16.99/$27.50, 288 pages.