How Napoleon secured the privileged place of Catholicism in France but reinforced Vatican’s control

How Napoleon secured the privileged place of Catholicism in France but reinforced Vatican’s control

Amid French Revolution, Napoleon Bonaparte, First Consul of France, and Pope Pius VII shared a common goal: to reconcile the church with the state. But while they were able to work together initially, formalising an agreement in 1801, relations between them rapidly deteriorated. In 1809, Napoleon ordered the Pope’s arrest.

Ambrogio Caiani reveals the tempestuous relationship between the emperor and his most unyielding opponent. After researching original finding in the Vatican and other European archives, Caiani uncovers the nature of Catholic resistance against Napoleon’s empire, charts Napoleons’s approach to Papal power and reveals how the Emperor attempted to subjugate the church to his vision of modernity and the struggle for supremacy between two great individuals and sheds new light as the conflict that would shape relations between the Catholic church and the modern state for centuries to come, changing Catholicism and the modern world.

This month the French senate approved legislation designed to reinforce the secular character of the state more than 12 centuries since Pope Leo III crowned Charlemagne Holy Roman Emperor, the tussle between earthly and spiritual power continues to roll the country.

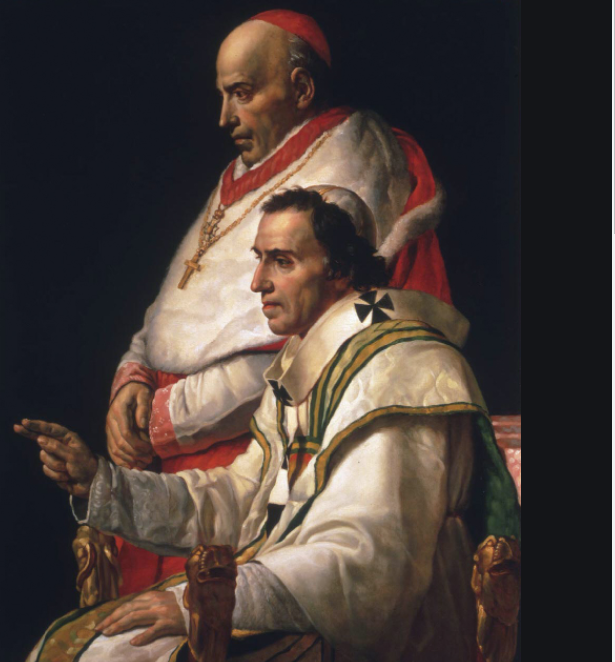

French republicanism was given birth during the 1789 Revolution and Napoleon’s desire to emulate and surpass Charlemagne symbolised the state’s tussle with the Church. Charlemagne had at least visited Rome, Pius VII was obliged first to come to Paris and then look on as Napoleon crowned himself. The emperor at the height of his power, trying first to charm the pontiff and then raging at him, hurling himself across the room and even smashing a porcelain vase in his anger. The Pope sits in silence through the onslaught, only puncturing the flow of the emperor’s verbiage with the two terse comments “Commediante!” ( comedian) and “Tragediante!” (tragedian). It was then the only occasion on which Napoleon met his match.

Before the Pope’s visit to Paris they had managed to negotiate a historic rapprochement between the Church and the post-revolutionary state, after it, Pius VII suffered years of imprisonment before seeing the tables turned and his tormentor defeated and sent into exile.

We now see that industrialisation, secularism, and the emergent nation-state spelt not the end of religious faith, but rather its transformation into a political force in its own right.

Napoleon Bonaparte had been born in 1769 in Corsica shortly after it had been conquered by the French: almost three decades his senior, Barnada Chiaramonti, the future Pius VII, came from a noble family from the town of Cesena. Both men too emerged into prominence unexpectedly at the end of the century. It was then, as Napoleon was sailing back to France from Egypt to become First Consul o the revolution, that Pope Pius VI, who had been arrested by French troops, died in captivity. This was a moment of great danger for the church and although not among the favoured candidate to succeed Pius VI, cardinal Chairamonti was the compromise candidate.

The first consul and the new Pope VII understood they needed each other. Napoleon saw religion as socially useful and the Catholic church as a stabilising force that had to be brought under the control of the French state while Pius VII, who as bishop has insisted that Catholicism and democracy were compatible, sought not merely to defend but even to extend Catholic influence. The historic Concordat of 1801 ratified the special relationship between the church and state in France.

For Napoleon the triumph reconciled French Catholics with the revolution, as well as paving way for the Pope to preside over his coronation as emperor in 1804 and later for his marriage to an Austrian princess, The Pope got a better bargain because the deal reinforced the Vatican’s control over episcopal appointments in France., and helping turn the papacy into the powerful institution it would become later.

To Kidnap a Pope: Napoleon and Pius VII by Ambrogio A Calani, Yale £20, 376 pages.