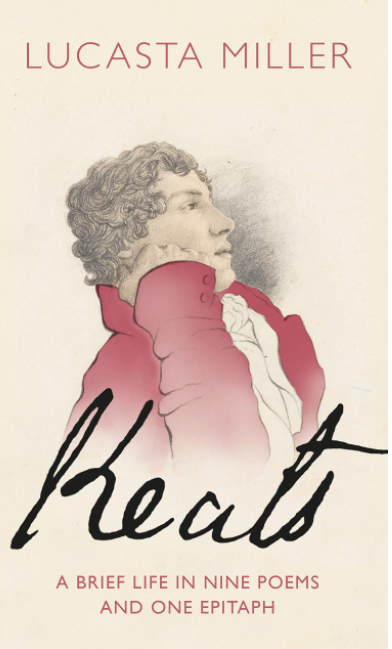

Keats “vertiginous originality”, marks the 200th anniversary of his death

Keats “vertiginous originality” as explained by Lucasta Miller.

Keats was trained as a doctor when he was 24 when he read his doom ( “my death warrant: I must die”) in a handkerchief spotted with bright arterial blood, John Keats died 200 years ago, aged 25, as his lungs were already so ravaged by Tuberculosis that the doctors in Rome – a warm climate offered a last faint chance of recovery.

Keats asked to be buried without an identifying name and with the poignant epitaph: “Here lies one whose name was writ in water.” After choosing these famous words Keats fell into a pleasant sleep, as his travelling companion Joseph Severn, conspired with the poet’s friend Charles Brown and John Taylor the publisher to enshrine them on the gravestone as an expression of “ the Bitterness of his Heart, at the Malicious Power of his enemies”.

Although the idea was Taylor’s, Brown later added words as a “ Heterodoxy”, and Severn, as an “eyesore”.

When Keats died having taken a battering from the conservative press, few critics imagined he would consider one of the great English poets two hundred years later.

Lucasta Miller resurrects the real Keats a lower-middle-class outsider from a tragic and dysfunctional family, whose extraordinary energy and love of language allowed him to pummel his way into the heart of English literature, a freethinker and a liberal at a time of repression, the ethereal figure of his posthumous myth.

Lucasta Miller reveals us how Keats made his poetry and explains why it retains its vertiginous originality and continues to speak to us across the generations.

Jane Campion’s 2009 film, Bright Star, in which a sensitive, nature-loving Keats was outshone by a maidenly Danny Brawne, weeping her eyes out at the news of his death before spending three nun-like years in widow’s weeds. The actual Fanny kept a live correspondence with Keats’s sister, her namesake, before marrying a much younger man and settling abroad as romantic biopics are scandalously keener on beauty than loyalty to truth.

Miller uses Keats’s best-loved poems to guide us from the dazzled explorer standing “silent, upon a peak in Darien” ( in his early “On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer”) to impressionable homage in “Bright Star” to Fanny Brawne: ( “I’ll imagine you, Venus, tonight”, Keats wrote to his capricious “Minx” from the Isle of Wight).

Miller as a fellow Hamstead Heather summons up a short, energetic, broad-shouldered young man who often jokingly signed himself as “Junkets” in controversial letters of Romantic Age.

Miller strolls across Hampstead Heath with Coleridge, his loquacious neighbour, we fell the older poet instantly invited him home or that Keats managed to resist the temptation.

Keats was eight when his father died, 14 when he cared for his dying mother, 23 when did the same for a beloved younger brother, to allow harsh reviews to hold him back.

He quit a burgeoning career in medicine for poetry which flowed with deceptive ease from what Keats once said, ”Teeming brain”.

Keats “Ode to a Nightingale” evokes images just as Schubert’s music uses notes, to express the indefinable. Ketas dismissing the glorious Odes and omitting the haunting “La Belle Dame sans Merci” from his third and final collection.

Yeats once summarised Keats as “ poor, ailing and ignorant”. Miller, however, follows Roe and remind us how wrong Yeats was. “ Poor”, when Keats siblings’ tangled legacy ( from the wealthy grandmother) inspired Dicken’s Bleak House account of the interminable Jarndyce vs Jarndyce case, “Ignorant” applied to a prize-winning scholar whose education at Charles Clarke’s renowned academy at Enfield outranked both Byron’s at Harrow and Shelley’s at Eton.

Miller reveals the myth, and help us to appreciate what she calls Keat’s “vertiginous originality”.

Keats: A Brief Life in Nine Poems and One Epitaph by Lucasta Miller, Jonathan Cape, £17.99, 368 pages.