Rise of autocracy in the name of democracy

How a popularly elected leader and tea boy has steered the world’s largest democracy toward authoritarianism and intolerance.

Narendra Modi, Hindu nationalism has been coupled with a form of national populism that has ensured its success at the polls, first in the western state of Gujarat and then in India at large- Modi managed to seduce a substantial number of citizens by promising them development and polarizing the electorate along ethno-religious lines. Modi related directly to the voters through all kinds of channels of communication in order to saturate the public space.

Christophe Jaffrelot, reveals how Modi’s government has moved India toward a new form of democracy, an ethnic democracy that equates the majoritarian community with the nation and relegates Muslims and Christians to second-class citizens who are harassed by vigilante groups. He shows how the promotion of Hindu nationalism has resulted in attacks against secularists, intellectuals. Universities, and NGOs. The government has centralised power at the expense of federalism and undermined institutions that were part of the checks and balances, including India’s Supreme Court.

Modi’s India is a sobering account of how a once-vibrant democracy can go wrong when a government backed by popular consent suppresses dissent while growing increasingly intolerant of ethnic and religious minorities.

Prime Minister Boris Johnson and his Indian counterpart Narendra Modi, had a virtual summit, at which the UK PM hailed a new era of mutual friendship. “The UK and India share many fundamental values. The UK is one of the oldest democracies in the world and India is world’s largest”.

Following his first election triumph in 2014, many hoped Narendra Modi would become a popular reformer, focused on rapid economic development. Instead, liberal critics describe a staunchly Hindu nationalist regime that has unsettled India’s minorities. Not the least its 200 million Muslims. Secularism enshrined in its constitution after independence in 1947, looks a spent force. New Delhi’s shift permanently to a more autocratic direction, taking 1.3bn people with it, global democracy itself would become a fringe political pursuit.

The economic reform also spawned the rise of a new “billionaire Raj” dominated by so-called “Bollygarchs”, as local oligarchs such as Mukesh Ambani and Gautam Adani are often known.

In George Orwell’s Animal farm ““No one believes more firmly than Comrade Napoleon that all animals are equal. But some are more equal than others”.

Modi’s many supporters, who see him as a leader capable of ushering India into a new period of national greatness.

Many in India see little to worry about in a future of ethnic democracy, pointing to the likes of Israel or Malaysia, whose democratic systems have some kind of state religion that reflects their dominant social group. India’s ties are improving even as the country’s democratic ranking have ebbed as its ties with the US and other European countries are now stronger than at any other time in living memory – again, because New Delhi sees them as useful given its own tussles with Beijing.

India’s future is far from certain but a return to an era of liberal secularism, embodied by leaders such as Nehru or even Modi’s predecessor, Manmohan Singh, looks highly improbable.

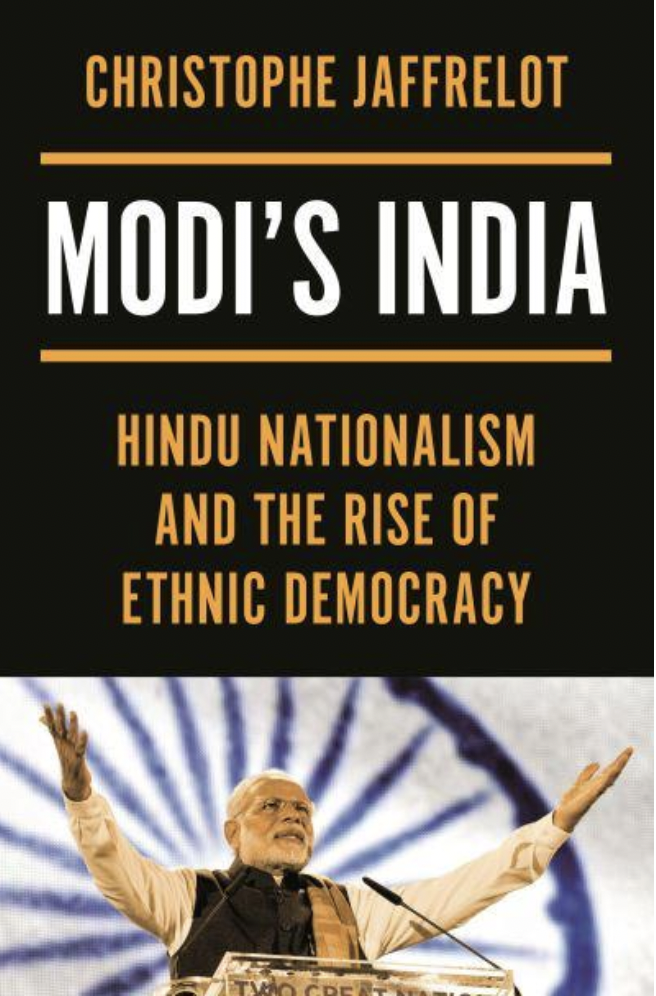

Modi’s India: Hindu Nationalism and The Rise of Ethnic Democracy by Christophe Jeffrelot, Princeton, £30, 656 pages