The prophet of language to the American people

Samuel Johnson a great lexicographer once said he loved all mankind except Americans, who he called pirates, robbers and rascals. The American dialect, the English they spoke revealed the “ corruption to which every language widely diffused must always be exposed.”

Thomas Jefferson saw the adulation of Johnson as an obstacle to America’s development and the republic needed to develop its own literature and language. He wrote in 1813, “ not needed by holding fast to Johnson’s dictionary, not by raising a hue and cry against every word he has not licensed but by encouraging and welcoming new compositions to its elements.”

US needed its own dictionary, one that portrayed several words its people had used to describe their landscape. At the age of 24, Noah Webster styled himself “ the prophet of the language to the American people”. The spelling books he introduced into American schools sold millions and his dictionaries eclipsed Johnson’s.

Webster’s dictionaries set a moral standard and wanted to fashion a distinctively American language and set about to reform English’s often absurd spelling. Why spell a word “believe” when it made more sense to write “beleev”? He would not include words like “fornication” and “ whore” unlike Johnson and would not draw on Shakespeare, whose rude words, Webster wrote ensured that “national language as well as morals are corrupted and debased by the influence of the Stage.”

The dictionary wars that waged by Webster and by George and Charles Merriam, the publishers who gained control of his dictionary against Joseph Worcester, a reserved scholar and complier of his own dictionaries, whom the Merriams falsely accused of plagiarism and fraud in their aim to ensure dominance of the Webster name.

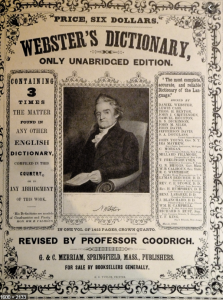

Webster’s 2000-page An American Dictionary of the English Language with a price of $20 first appeared in 1828, which was heavily borrowed from Johnson although it contained American spelling changes such as Theater, traveling and ardour. The slimmed-down version was published in 1829 which Webster loathed it thinking it made his original look like a first draft.

After Webster’s death in 1843, the Merriams gained control of the dictionary and planned a second edition and continued polemics against Worcester and his subsequent dictionaries unwilling to see anyone prevail against the new unabridged edition of Webster’s dictionary in 1864. In 1994, the US courts held that “ Webster” has become generic.

The Dictionary Wars: The American Fight Over the English Language by Peter Martin, Princeton £24/ $29.95, 368 pages.