An enthralling narrative alternative history of the Italian Renaissance

In 1529, two English envoys Sir Nicholas Carew and Richard Sampson filed a report after travelling to Bologna for Charles V’s coronation as Holy Roman Emperor, saying in towns and villages, they saw children crying about the streets for bread, and yea dying for hunger, Pope Clement VII told them that “war, famine and pestilence” had raged so ferociously across Italy that it would be many years before the peninsula, “ Shall be anything well restored for want of people”.

Although Francesco Guicciardini, the great Florentine historian wrote in the 1530s claiming that “ Italy had never enjoyed such prosperity, or known so favourable situation as that in which it found itself so securely at rest in the year of our Christian salvation of 1490, and the years immediately before and after”.

King Charles VII of France invaded the Italian peninsula in 1494 to press his claim to the realm of Naples, as the invasion turned into a permanent battleground among the armies of France, Spain and the Holy Roman Empire, the peninsula’s small, squabbling states and assorted mercenaries.

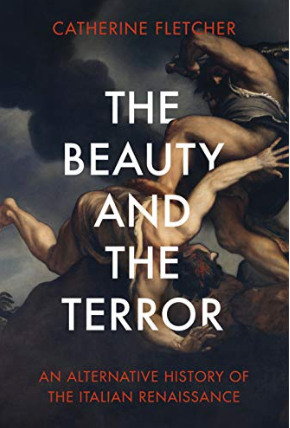

The wars ended with the imperial sack of Rome in 1527, a saturnalia of destruction that contemporaries recalled as “God’s vengeance on a corrupt city and the failing papacy, although this was an era of extraordinary artistic achievements, the age of Leonardo da Vinci, painted the Mona Lisa and Michelangelo painted the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, the effort which left him bending like a Syrian Bow, Raphael and Titan, Machiavelli and Castiglione” Catherine Fletcher, a professor at Manchester Metropolitan University, writes in The Beauty and the Terror.

Fletcher tends to focus on the genius and glory at the expense of the atrocities.

We revere Leonardo da Vinci for his art although few appreciate his ingenious designs of weaponry and we know the Mona Lisa for her smile but not that she was married to an upwardly mobile and ruthless silk merchant and slave trader, Francesco del Golcondo, who had operations in mainland Portugal and Madeira. He brought enslaved women, most likely from Africa to be baptised in Florence in the 1480s and 1490s. Italians financed and led some of the early transatlantic voyages to the New World. After the Genoa-born Christopher Columbus, “out of Italy came finance, Individuals, a history of enslavement and ideas about running colonies, a framework of understanding the conquered lands, from the papacy –religious legitimation for colonial projects via papal bulls and interpretation of canon law.

When we visit Florence to see Michelangelo’s David but not hear of any massacre that forced the republic’s surrender in focusing on the Medici in Florence and Borgias in Rome and also miss the vital importance of the Genoese and Neapolitans, the courts of Urbino and Mantua. We rarely hear of the women writers, Jewish merchants, the mercenaries, Engineers, prostitutes, farmers, and citizens who lived the Renaissance every day.

For decades, a series of savage wars dominated Italy’s political, economic, and daily life, generating fortunes and new technologies, but also ravaging populations with famine, disease, and slaughter.

The same short time, the birth of Protestantism, Spain’s colonisation of the Americas and the rise of the Ottoman Empire all posed grave threats to Italian power, while sparking debates about the ethics of government and enslavement, religious belief and sexual morality.

The Beauty and the Terror: An alternative History of the Italian Renaissance by Catherine Fletcher, The Bodley Head £25, 432 pages.