School of high achievers

The state sponsored “ Friend of the Coconut Tree” is a school for higher achievers – over 30meters high that is – has recently been founded in India’s southern state of Kerala , where over 1400 youngsters have graduated and have become part of the dial-a-coconut-tree-climber service across the province.Spread across 10 districts and backed by the provincial Coconut Development Board, the programme aims, during its six days, to train some 5,000 coconut cutters to harvest the fruit.

Kerala has over 500 million coconut trees covering 40 per cent of its total area. Over the years, a shortage of skilled cutters to harvest them forced growers to employ largely unskilled migrant labourers at exorbitant amounts for unsatisfactory service.

“The scarcity of skilled gatherers had also severely disrupted their harvesting cycles leading to a loss of income for the growers” said Srikumar Poduwal head of the board’s training programme for coconut harvesters in the coastal city of Kochi (formerly Cochin) in southern India.

Instead of the recommended harvesting cycle of 45-60 days, farmers were reaping the fruit only once every three to four months but the training was going to transform that situation, Poduwal said.

Kerala has the highest literacy rate in India at 97 per cent. Many of its young people armed with a good education have, over the past four decades, migrated overseas – mainly to the Gulf region – in search of better-paid work.

Those who stayed behind tend to seek office jobs and regard coconut-picking as menial and less-rewarding work.

Traditional coconut-cutters earned higher wages for less demanding work in the construction boom triggered by vast sums of money sent back home by expatriates. As a result, there were not enough hands left to pick the cash crop. On numerous occasions, it ended up withering at the root.

Several coconut-harvesting devices to replace trained palm tree climbers were developed by individuals, research institutions, universities and many non-governmental organisations have in the past proved woefully inadequate.

The only alternative was to revive the coconut harvesters.

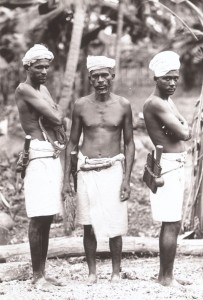

Dressed in a loin cloth and armed with machete, vattu kati, the professional tree climbers race up palm trees 20- 30m tall, by embracing the trunks using the soles of their feet to propel themselves upward at great speed.

Once on top, a seasoned cutter trims the branches surrounding 30-40 coconuts per tree and lops off the fruit, taking no more than three to four minutes.

In an eight-hour, back-breaking shift, skilled climbers are capable of harvesting 50 palms or some 2,000 coconuts for which they are paid Rs 1,000 (£11).

Overhead costs for the training schools are negligible.

The “classrooms” are largely local coconut plantations and many of the teachers are volunteers from the local Tandan tribe of traditional coconut-pickers and Coconut Development Board experts. The cutters also learn about spraying and pest control, plant-protection measures and identification of tender nut, mature coconut and seed nut.

There is no tuition fee and, in many respects, the training schools can be regarded as promoting the dignity of labour.

There is, however, no equality when it comes to the sexes in the coconut-harvesting profession. Women are not allowed to enrol as it is too arduous a task for them.

And donning skimpy loin cloths would doubtlessly cause problems.

“In Kerala women prevail in all spheres of life,” said Roshin Varghese, whose family owns a coconut plantation in Kerala.

She was referring to the matriarchal system that exists among many communities in the province.