Women were not able to reach their full potential

In the 1970s when social historian Jane Robinson was at high school, there were only four options for British girls to fill up the time between leaving education and getting marries – secretary, nurse, teacher, and hairdresser.

Robinson who wanted to go to university despite discouraging career adviser saying “ a degree was no guarantee of job satisfaction or even a job. Why bother?”.

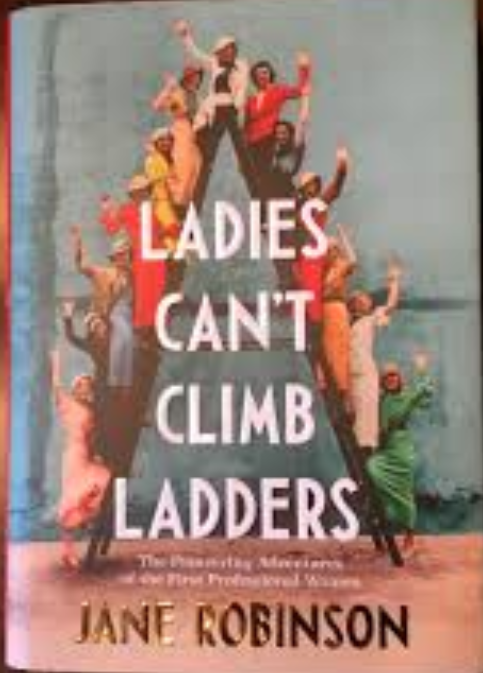

Robinson in her book Ladies can climb ladders reveals the lives and struggles of female pioneers in the British professions in the early 20th century, especially in the fields of medicine, engineers, clergy and academics, architects and lawyers.

In her book, she explains the fight for women’s admission to higher education, and students who got this chance to shine leading to then undesirable consequences of self-determination, economic independence, and ambition.

The cultural norms that prevented women’s progress at every stage, like lack of suitable lavatory provisions.

In 192, Gwyneth Bebb Thomson, who had studied Jurisprudence at St Hug’s Hall, Oxford, sued the Law Society for refusing to admit women to train for legal profession, “Had she been a man, Gwyneth’s exam results would have pocketed her a first-class degree and she would have been acknowledged as the highest achiever for her year”. As women were not allowed to receive degrees, Bebb Thomson had no letters to her name.

She not only lost her case against the Law Society, but also lost an appeal, on the grounds that “ as women had never been admitted before, there was no precedent, and without a precedent, they could not be admitted.”

The flood gates only opened after the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act of 1919, and the advent of the first world war, when women had tasted independence as they took up work of men away on the front, and passing of partial suffrage. The act sought to remove the bar from women joining the professional workforce.

Eventually, Bebb Thomson and others did gain entry to the Inns of Court while medical schools and other training grounds like the civil service also opened up although the latter stated that women should not be paid the same as men, even if occupying a similar position or grade”.

In the book the civil service commissioner wrote in 1918, “ Do you think that merely because a woman is equal to a man in competitive examinations, therefore she is his equal or vice versa? It is like comparing Chinamen with Englishmen or Hindus with Englishmen or Hindus with Chinamen.”

Although the opportunities may have opened for women, the culture inside was still hostile as women endured many humiliations as male colleagues sought to isolate them. Archaeologist, Margaret Murray, was made a fellow of University College London in 1922, where female academics were segregated in a common room so small that it was “later promoted to become a cloakroom. After inventing the provost to tea, they were upgraded to a larger space a former lab full of broken equipment where the coffee was brewed in the stink cupboard.

Women of all temperaments and economic backgrounds are continuing to fight for professional recognition and personal fulfillment.

Ladies Can’t Climb Ladders: The Pioneering Adventures of the First Professional Women by Jane Robinson, Double Day £20, 368 pages.